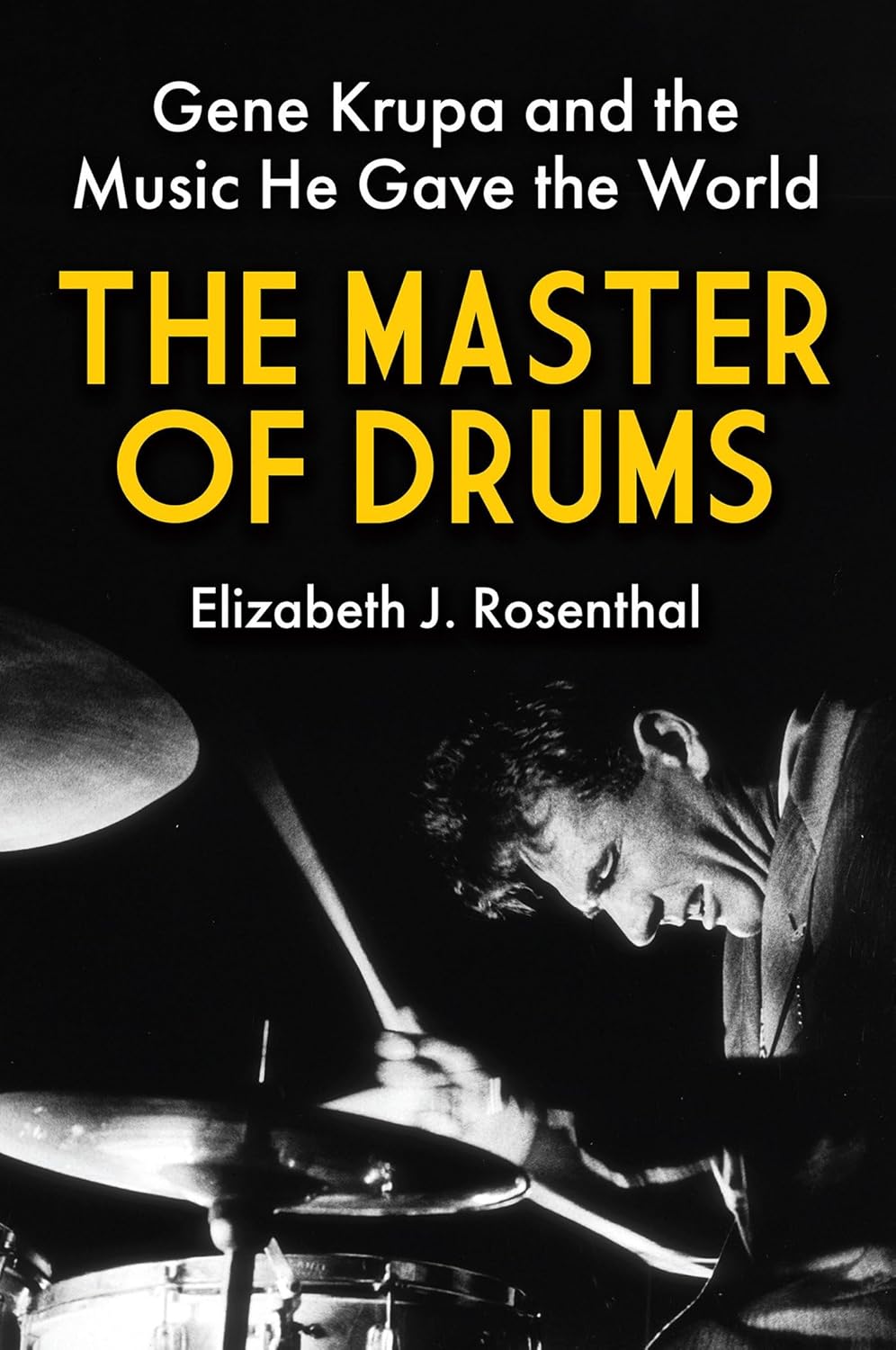

Home » Jazz Articles » Book Review » The Master of Drums: Gene Krupa and the Music He Gave The World

The Master of Drums: Gene Krupa and the Music He Gave The World

Krupa was a genius masquerading as an ordinary guy. And that essence, for certain, Elizabeth Rosenthal captures very, very well.

The Master of Drums

The Master of Drums Elizabeth J Rosenthal

320 Pages

ISBN: 978-0-8065-4320

Kensington Publishing Company

2025

In the interests of full disclosure, I spent an extended period with Gene Krupa as an adolescent. Relatives were friends of Krupa's. All the nice things Elizabeth J. Rosenthal says about Krupa as a human being were their constant refrain. If you think maybe Krupa, in Rosenthal's handling, sounds to good-to-be-true, well, maybe he was. Not a saint, for sure, but a genuinely good guy. As far as I know, he was. Rosenthal has gotten that right.

In Krupa's own estimation—his own words—his major accomplishment was "to make the drummer a high priced-guy." That is, to be fair, not an inaccurate appraisal, but, clearly, one that was all too modest. How, one asks, did this Polish American kid, become not only a matinee idol (good looks certainly helped) but a technically innovative player who, in his own way, shaped the modern concept of jazz drumming—at least in its swing evolution—as Louis Armstrong did the trumpet, or Benny Goodman the clarinet. Well, the old joke about getting to Carnegie Hall is not misleading: he practiced. He watched. He took lessons from everyone from classical tympanists to Indian percussionist Vishnudras Shirali and Zulu drummers at the 1939 World's Fair. And then he practiced some more.

For a guy who did not read music until he was well into his professional life, Krupa also authored a classic method book. He also pioneered using four limb independence, which someone described as "man, when he's going, he's got both hands, both feet, and both cheeks going different ways." Ok. This was a Westinghouse machinist's description of Krupa's technique—not some conservatory-trained percussionist's, but who could do better? Perhaps as much as Goodman lived the clarinet or John Coltrane the tenor sax, Krupa lived the drums, as much an expression of elan vital as a way of making a living. No exaggeration, Duke Ellington got it wrong. A drum was not a woman. It was Gene Krupa.

Speaking of Ellington, there is, of course, the very real and fraught question of the importance of black drummers when segregation not only produced a color line, but brutal lynchings. Krupa was not kidding anyone about his relations to black drummers, especially Chick Webb, whom he adored, or Zutty Singleton whom he watched obsessively as a young apprentice in Chicago when Krupa was still a teenager. "I could see this little face about every night," Singleton recalled. Lessons are where you find them. Krupa hung with black drummers, played with black drummers, and learned from black drummers, instrumentalists and arrangers. And then he brought his own stuff, especially from the European classical repertoire. You can hear someone say, "yeah, all over the kit, but no time." Quite honestly, not too many professional drummers of any color who would offer a similar assessment. And Rosenthal's narrative is full of many great modern drummers, a few not known for their modesty, who would tell you otherwise. A showman? Absolutely. That was part of the package. Rufus "Speedy" Jones or Sonny Payne was not?

Krupa, of course, was not simply a drummer. He was a bandleader; he too made the hazardous transition from swing to bop. Krupa had good bands, very good bands, but perhaps never a great one. He brought on trumpet player Roy Eldridge when he literally had to risk life and limb (his own, not just Roy's) to feature him. And there was singer Anita O'Day, whom Krupa called "a wild chick." She got her start with Krupa, the beginning of a major career. It is less certain whether Krupa never fired anyone, as he insisted (trumpeter Shorty Sherock may have taken "ill" at Roy's presence, but he was not happy that Roy replaced him). That he was all too human is demonstrated by O'Day, whom he propositioned, but sprang to his defense when a 1943 marijuana drug charge nearly ended his career: Anita said, correctly, he was a Scotch drinker, not a stoner. Krupa was very fortunate to have had personal and professional support at a very difficult time. Put-up job or not, Krupa's was a very desirable scalp, one that ambitious politicians and prosecutors could rarely resist, especially in California, where a host of major bop musicians, from Hampton Hawes to Charlie Parker got similar treatment, or even worse.

Once he was back on his feet, Krupa had another band—or bands, because one had a string section—but in the late 1940s, Krupa too had a bop band—like Artie Shaw and Benny Goodman. Rosenthal argues that Krupa was a precursor to many modern styles of drumming, including the use of bop "bombs" (occasionally) a la Kenny Clarke. And, by dint of his enormous exposure, would influence rock drummers like Neil Peart too. But this needs to be put in perspective. Red Rodney, who joined Krupa's late band, may very well have been, along with Don Fagerquist, who was also with Krupa, one of the serious white bop trumpet players. And Rodney once said he wanted to play like Harry James. Who did not want to play like one of his or her idols? That is all too natural for a novice player. But Krupa was no more a seminal bop player than James was. And, for that matter, hip arrangers like Eddie Finckel or Gerry Mulligan sometimes counted for less than the addition of a key sideman to his band, like saxophonist Charlie Kennedy, who seems to have worked wonders in the rhythm department when he joined the reeds. Krupa's bop bands were good, but not up to the level of say, Woody Herman's. As for rock drumming, Krupa was known to refuse audience requests to play "Wipe Out." "I wouldn't know how," he answered. Krupa was a nice man and a great performer, but he was not a clown.

For many star performers, the downside of their careers often turns into a search for relevance. Krupa seems to have been spared this depressing phase, in no small part because changing musical tastes notwithstanding, many continued to seek him out. He was at least financially secure. He toured extensively with Jazz at the Philharmonic in the early and mid-1950s and then settled in for extended gigs at the Metropole in New York City and sessions at the Steel Pier in Atlantic City. He continued to occasionally perform in clubs in South Jersey that required not much more than a two-hour drive from his home in New York, and some trips further away. But his health had begun to fail him, he had several heart attacks, emphysema, and finally, chronic myeloid leukemia. There was one last heroic reunion with Benny Goodman at Carnegie Hall in 1973. By then, at sixty-four, he was gone. He had probably played himself to death.

This is a biography that is worthy of its subject. Gene Krupa was a remarkable musician and a remarkable man. He had his flaws, obviously, but a lack of sense of what his playing, music and even presence could do for others was not one of them. Krupa was a genius masquerading as an ordinary guy. And that essence, for certain, Elizabeth Rosenthal captures very, very well.

Tags

Book Review

Richard J Salvucci

Publisher

Gene Krupa

Louis Armstrong

Benny Goodman

John Coltrane

duke ellington

Chick Webb}, whom he adored, or {{Zutty Singleton

Rufus Jones

Sonny Payne

Roy Eldridge

Anita O'Day

Shorty Sherock

Hampton Hawes

Charlie Parker

Artie Shaw

Kenny Clarke

Neal Peart

Red Rodney

Don Fagerquist

Gerry Mulligan

Charlie Kennedy

Woody Herman

New York City

Carnegie Hall

Comments

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.