Home » Jazz Articles » Groove Orbit » How Creedence Clearwater Revival Saved Jazz

How Creedence Clearwater Revival Saved Jazz

Creedence Clearwater Revival—a band rooted in swamp rock, rhythm and blues, and Southern gothic Americana—became the unlikely financial engine behind one of the most ambitious jazz preservation efforts of the 20th century.

To understand their place in jazz history, it helps to go back to the beginnings of their label, Fantasy Records. Jazz trombonist Jack Sheedy started Coronet Records, an independent San Francisco-based jazz label. Although the Coronet catalog focused primarily on Dixieland, it also produced the earliest recordings of Dave Brubeck.

Unfortunately, Sheedy was unable to keep the label afloat, so in 1949, he sold it to brothers Max and Sol Weiss, who owned a pressing company called Circle Records. They renamed the label Fantasy to capitalize on the public's growing interest in science fiction and fantasy, and much of its early catalog featured jazz artists.

Dave Brubeck turned out to be a major asset for the fledgling label. While his albums sold well, his association proved to be short-lived due to a contractual misunderstanding. When he signed on, Brubeck believed he would receive 50% of the label's total revenue. However, when he discovered that the deal only granted him 50% of his own record sales, he felt misled and left Fantasy for Columbia Records.

Despite this setback, the label continued to grow. Jazz was still wildly popular during the 1950s, and Fantasy artists such as Vince Guaraldi and Cal Tjader had respectable sales. In addition to jazz, the label earned income from comedy albums by artists such as Lenny Bruce.

But everything changed in the early 1960s. The Beatles' 1964 appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show marked a seismic shift in American music tastes. Jazz, once dominant, was suddenly being pushed to the margins as rock and roll took over the airwaves. Practically overnight, a flood of British performers—The Beatles at the forefront—dominated the American charts, and garage bands started popping up everywhere, ushering in a new era in popular music.

One of the bands swept up in the rock and roll craze was a group from nearby Cerritos, California, called the Blue Velvets. They were playing local gigs, looking for a break. That break came in 1964, when guitarist John Fogerty saw a television program titled Anatomy of a Hit, which featured Vince Guaraldi, who had recently scored a hit with "Cast Your Fate to the Wind" (Fantasy 1962).

Fogerty drove the ten or so miles into San Francisco and knocked on Fantasy's door. He told them he had seen the show and asked, "Would you like another hit?" The Blue Velvets initially approached the label to record instrumental songs, but Fantasy saw an opportunity to cash in on the British Invasion. Instead of thinking about the music, the label saw dollar signs.

They signed the group to a subsidiary label called Scorpio and brought in John's older brother Tom as lead vocalist. Without consulting the band, the label changed their name to The Golliwogs, thinking it sounded "British." The band hated the name. To make matters worse, they were asked to wear fuzzy white wigs, which made them look ridiculous.

The formula flopped. Despite producing some excellent garage rock—much of which would later be reissued—The Golliwogs failed to chart. Still, the group maintained a close relationship with the label. John Fogerty even took a job in the warehouse.

By 1967, Fantasy's sales were slumping. After several failed deals, the Weiss brothers sold the label to marketing director Saul Zaentz, who signed a new contract with the Fogerty brothers. Zaentz convinced the band to rebrand, ditching the Golliwogs image and updating their sound to better align with the emerging counterculture. Even though they weren't part of the hippie scene, the band was happy to shed the old identity. After tossing around ideas, they settled on a new name: Creedence Clearwater Revival.

By the end of the 1960s, Creedence's meteoric rise would prove to be Fantasy's salvation. Between 1968 and 1972, they released a string of hit albums and singles that dominated the airwaves. Bayou Country (Fantasy 1969), Green River (Fantasy 1969), Willy and the Poor Boys (Fantasy 1969) and Cosmo's Factory (Fantasy 1970) weren't just critical successes—they were blockbusters. It seemed as if every kid in America owned at least one Creedence album. By the end of the decade, their records were outselling The Beatles—all without having to wear goofy wigs.

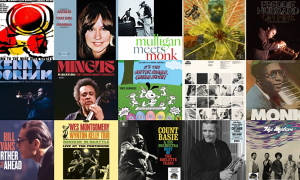

By the early 1970s, Creedence was one of the top-selling acts in the world, and all that revenue was flowing straight into the coffers of Fantasy Records. What had once been a modest jazz imprint was now in a position to expand aggressively—especially in jazz. Under Zaentz's leadership, Fantasy began acquiring independent jazz labels struggling to survive in a rapidly changing industry. In the early 1970s, Fantasy bought Prestige Records, home to classic recordings by Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Sonny Rollins, and Thelonious Monk. Soon after, they acquired Riverside Records, whose catalog included essential work by Bill Evans, Cannonball Adderley, and Wes Montgomery.

Fantasy later brought Milestone and Pablo Records into the fold, further expanding its jazz empire. The company's red-brick headquarters at 10th and Parker Street in Berkeley became known as "The House That Creedence Built." Inside its walls, jazz classics were being remastered for reissue, and new sessions were arranged for veteran artists sidelined by the industry's shifting trends. Bill Evans and Sonny Rollins continued to release new material through Fantasy and its subsidiaries, and younger jazz musicians benefited from the label's renewed commitment to the genre.

Practically overnight, Fantasy had become the steward of one of the world's largest and most important jazz catalogs—thanks largely to the phenomenal success of a rock band that seemed worlds apart from jazz. Creedence Clearwater Revival—a band rooted in swamp rock, rhythm and blues, and Southern gothic Americana—became the unlikely financial engine behind one of the most ambitious jazz preservation efforts of the 20th century. Without them, it's entirely possible that much of this music would have gone out of print or remained buried in the vaults. Fantasy didn't just survive the rock revolution—it adapted, thrived, and in doing so, became one of the most important jazz labels in America.

The label's success, however, has not been without controversy. For years, John Fogerty fought legal battles over the rights to his music. At one point, he refused to perform Creedence songs live. In a particularly surreal moment, Fantasy even sued him over his 1985 hit "The Old Man Down the Road" (Warner Bros), claiming it sounded too much like "Run Through the Jungle" (Fantasy, 1970)—a song Fogerty himself had written.

Controversy aside, many of the recordings preserved and reissued by Fantasy remain vital parts of the jazz canon. Thanks to Creedence Clearwater Revival—along with the vision of Saul Zaentz—Fantasy not only weathered the storm of the rock and roll revolution but helped ensure that the sounds of Coltrane, Davis, Rollins, and Evans would resonate for generations to come.

Tags

History of Jazz

Kyle Simpler

Creedence Clearwater Revival

Dave Brubeck

Vince Guaraldi

Cal Tjader

The Beatles

Miles Davis

John Coltrane

Sonny Rollins

Thelonious Monk

Bill Evans

Cannonball Adderley

Wes Montgomery

groove orbit

Comments

About Creedence Clearwater Revival

Instrument: Band / ensemble / orchestra

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.